Blogs

Spotify gives teams autonomy so that mistakes can be made faster

Rolf-Christian Wentz

Jan 12, 2023

7 min read time

“We strive to make mistakes faster than anyone else,” says Daniel Ek, founder of the Swedish music streaming company Spotify. Ek’s rationale: to create something really great, you will inevitably make mistakes. But you can learn from every failure. So failing fast also means learning fast and therefore improving fast. Speed is essential. For Spotify, this is a long-term strategy for success.

Spotify’s streaming innovation

Spotify was founded on July 14, 2006 by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon in Stockholm. Both are serial founders of Scandinavian online start-ups. Ek was previously CEO of uTorrent for a short time, which made money from pirated music and films on BitTorrent. Ek and Lorentzon develop the vision of a company that makes music available to customers just as easily as pirated music, but in a legal way. In October 2008, they were ready. They were able to convince most of the world’s largest companies holding music rights, such as Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group, of their idea and launched their streaming service in Sweden. They are pursuing a freemium business model, i.e. there is a free streaming version with advertising and a paid premium version that offers users advantages in terms of the number of accessible music tracks, sound quality and offline use in addition to the absence of commercial breaks. After the launch, business took off. When Spotify is launched in the USA in July 2011, it already has more than 10 million registered users, including 1.6 million paying subscribers, and is valued at US$ 1 billion.

Spotify’s agile team organization and way of working accelerates innovation

One of Spotify’s success factors – in addition to its fault-tolerant culture – is its agile corporate structure and way of working, which allows Spotify to move quickly. Initially, the Spotify team is essentially characterized by its SCRUM-based working method. A few years later, however, Spotify has grown into a group of teams and realizes that some of the standard SCRUM practices are getting in the way of progress. Spotify decides to make SCRUM optional. Agility is more important than SCRUM, and agile principles more important than certain practices. Spotify renames the role of SCRUM Master to Agile Coach. Instead of SCRUM teams, we now talk about squads. A squad is a small cross-functional, self-organizing team. Autonomy is the main driving force behind squads. The members of the squads have end-to-end responsibility for everything they create: Design, deployment, maintenance, operations. Autonomy means that the Squad decides what to build, how to build it and how to work together. Instead of standardizing methods, Spotify relies on the exchange of ideas between squads. Squads let themselves be convinced by other squads and adopt new methods if their colleagues are successful with them. In the same spirit, Spotify has created an open source model for programming code. Squads can easily adopt code from other squads and thus complete their software more quickly. Spotify encourages small and frequent releases. The autonomy of the squads even goes so far that squads can release a new release independently without having to coordinate with the other squads. To this end, Spotify has rebuilt the IT architecture in such a way that decoupled releases are possible. Of course, there are a few limits for each squad, such as the squad’s specific mission, the general product strategy for its product area and the short-term goals, which are renegotiated by the squad every quarter. And for all the autonomy that the Squads have, it is important to Spotify that all Squads are aligned to the same Spotify corporate vision and goals. The Squads are therefore, as Spotify calls it, loosely coupled but tightly aligned. Spotify does not see tight alignment and Squad autonomy as opposites. Rather, it is the tight alignment of the teams to the same corporate vision and the same corporate goals that allows the squads to be given so much autonomy. Innovation at Spotify is therefore bottom-up. It fuels the company’s rapid growth. The agile, autonomous squads do not need approval from the top of the company to test out a new idea. The “Discover Weekly” innovation illustrates this very well.

The “Discover Weekly” innovation

In March 2015, Chris Johnson and Ed Newett meet with Matt Ogle and present their innovative idea to him. All three work in the Spotify office in New York. Chris Johnson has a PhD in Computer Science and Machine Learning from the University of Austin, is now Machine Learning Manager at Spotify and leads a team of machine learning engineers, data engineers and software engineers. Ed Newett has a Master of Science from the Georgia Insitute of Technology and is now Lead Software Engineer, Music Discovery at Spotify. Matt Ogle has a Master of Arts in English and Computer Science from the University of Alberta and now works for Spotify as Senior Product Owner, What To Play. Johnson and Newett have been thinking for a long time about a problem that Spotify has not yet been able to solve satisfactorily: How can users discover the music they really love in a library of millions of songs without having to waste a lot of time listening to music they don’t like? Spotify did develop solutions in 2013 and 2014 with “News Feed” and “Discover”, which provide users with personalized music recommendations. But users still have to spend an unnecessary amount of time and effort to finally discover and enjoy their favorite songs. With their proposal, which will henceforth be called “Discover Weekly“. Johnson and Newett want to remove all the inconvenience for users when discovering new favorite music. What if Spotify sorted the music you’ve listened to in the past into artist clusters and micro-genres based on technology from Echo Nest, a music analytics company Spotify bought in 2014? What if Spotify analyzed the two billion or so playlists that all other Spotify users have created and algorithmically matched their preferences with your playlists so that Spotify could then suggest a new playlist specifically designed for your tastes? What if Spotify sent you a new personalized playlist every week? Ogle likes Johnson and Newett’s idea. He brings in a colleague to play the role of advocate diaboli to find potential holes in the idea. The ensuing discussion helps to make the idea even more concise and improve it further. Within a few weeks, Johnson and Newett’s squad had developed an initial prototype. This was possible in such a short time because Spotify had already collected data from its 75 million active users, defined micro-genres of music and classified all the tracks in its immense music library accordingly.The prototype of “Discover Weekly” uses artificial intelligence technologies such as collaborative filtering, natural language processing, deep learning and neural networks. It is the first to be tested by Johnson and Newett’s colleagues, who are all active Spotify users. The colleagues love “Discover Weekly”! Following this in-house experiment, the Squad undertakes another quick test, this time on one percent of active Spotify users, or nearly one million customers, using an A/B test to test two versions of Discover Weekly against each other. Here too, the response was overwhelming. 65% of respondents find a new favorite song in their personalized weekly playlist. Based on this data, Spotify’s management decided to roll out “Discover Weekly” worldwide. Scaling the “Discover Weekly” algorithms from one million users to all 75 million users, in 21 languages and in several time zones for delivery every Monday morning, proves to be a major challenge. But the roll-out was successfully completed in July 2015. “Discover Weekly” is a huge success. Spotify gains an enormous number of new customers. They are amazed. One of the users, Dave Horwitz, writes; “It’s scary how well the Spotify ”Discover Weekly“ playlists know me”. And Abbey Dighans chimes in: „Discover Weekly knows me better than I know myself“.Spotify concludes: “We believe that a key differentiator between Spotify and other audio content providers is our ability to predict music … that our users will enjoy”.

Spotify’s innovative mitigation of errors

Innovations such as “Discover Weekly”, which are developed and rolled out by autonomous squads at great speed, enable Spotify to hold its own against massive competition and keep even such financially strong companies as Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited and YouTube Music at a distance. Spotify is aware that it must mitigate the consequences of mistakes, despite its fault tolerance towards autonomous teams (Kniberg-2 2014). It therefore focuses on proactive risk management, rapid subsequent troubleshooting and postmortems or retrospectives in order to learn from mistakes. Mistakes must never pose a fatal risk to the company. This is why Spotify works with the concept of a “limited blast radius”. Releases happen continuously at Spotify, and they are small. Due to the decoupling of the releases of the individual squads, a bug in a squad will never affect the entire Spotify software, but only a section of it. And the squad has usually fixed its error quickly. And if the error cannot be fixed so easily, the release, which is small, is simply rolled back. In addition, a new release is only activated in stages. In the first step, only a very small number of users receive the new software. Only when it is running smoothly and stably will it be made available to all users in stages. In this way, Spotify can encourage its employees to experiment without taking an uncontrollable risk for the company.

Spotify secures its market leadership

Spotify secures its market leadership

To date, Spotify has managed to remain the world’s leading music streaming company. In its prospectus for the New York Stock Exchange on February 28, 2018, Spotify reported 159 million monthly active users and 71 million premium subscribers. Spotify goes public on April 3, 2018 and reaches a company valuation of more than USD 30 billion in August of that year. In its annual report for 2019, Spotify then reported 271 million monthly active users and 124 million paying Premium subscribers as at December 31, 2019. Despite sales of US$ 6.8 billion in 2019, Spotify is not yet profitable, however, but is still making an operating loss of US$ 73 million.

Dr. Rolf-Christian Wentz

Sources:

- Wentz RC (2020) Die neue Innovationsmaschine, Kindle Direct Publishing

- Kniberg-1 (2014) Spotify Engineering Culture – Part 1 of 2, Januar 2014, at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GK1NDTWbkY

- Kniberg-2 (2014) Spotify Engineering Culture – Part 2 of 2, April 2014, at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOt4BbWLWQw

- Kniberg-3 (2015) Scaling Agile @ Spotify with Henrik Kniberg, at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyZEikKWhAU

- Elberse A, de Pfyffer A (2016) Spotify, Case 9-516-046, Harvard Business School, Boston

———————————————————————————————————-

Innovation machines like BMW, Google or Apple organize chance encounters through architecture

Rolf-Christian Wentz

Jan 4, 2023

4 min read time

We need to acknowledge the reality that many great innovation ideas and innovations are the result of chance encounters. Ideas often emerge when people from different functions, business units or companies meet, share their different perspectives and their half-baked ideas, and possibly complete them into a complete innovation idea. What organizational conditions can innovation management create to increase the frequency of such encounters and the likelihood of serendipity? What role can innovation management through architecture play here?

Innovation management using architecture: How BMW and Google organize their innovation management

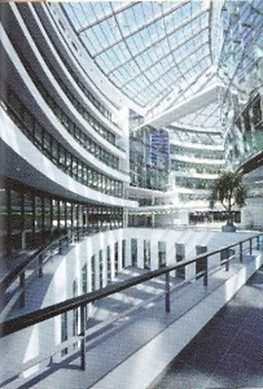

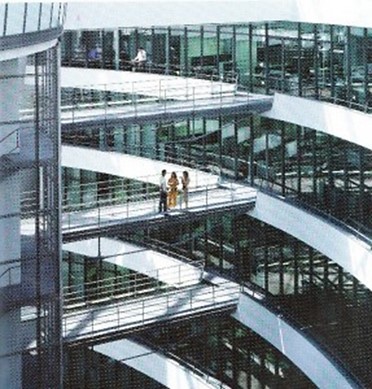

In addition to organizing short-term meetings of employees with the help of events such as innovation fairs, the architecture of the buildings plays an important role as a long-term measure in promoting chance encounters and unplanned collaborations and thus in innovation management. Architects such as Gunter Henn, who designed BMW’s futuristic “Project House”, completed in 2004 and integrated into BMW’s Research and Innovation Centre (FIZ), for BMW’s interdisciplinary product development teams, argue that organizational structure and physical space work together to influence communication patterns and thus innovation. In BMW’s Project House, project activities take place in the interior space in the center of the building. The departments, on the other hand, are housed in an outer ring, which is connected to the project space via several busy bridges. This architecture signals that the projects are “boss” and encourages connections and chance encounters, visual contact and broad awareness in the organization about the status of the various innovation projects.

Figures: Promoting chance encounters in BMW’s project house (Source: Allen, Henn 2006)

Other long-term building architecture measures to encourage chance crossings include creating a dedicated canteen where colleagues can meet at lunchtime, or deliberately limiting the number of entrances and exits in buildings to increase the likelihood of employees crossing paths and having chance encounters. Google has equipped all floors in Mountain View with several so-called micro kitchens, where Googlers can get coffee, fruit or snacks, relax and chat. Google has deliberately placed these micro kitchens in the middle between two different innovation teams in the hope that the members of these two teams will have chance encounters and get talking to each other. This builds on Google’s realization that the best innovation ideas flow at the interface between different innovation teams.

We have now seen how BMW and Google practice long-term innovation management using architecture. But other companies are also pursuing this approach.

Innovation management through architecture: Apple, Pixar and Disney also increase the chance of chance encounters and innovation through architecture

Pixar and Apple’s Steve Jobs was also a staunch advocate of the importance of architecture for chance encounters, innovation and collaboration: “If a building doesn’t encourage that, you lose a lot of innovation and the magic that is triggered by serendipity,” he explained. When he designed the architecture of Pixar’s new headquarters, he equipped it with a central atrium to motivate Pixar employees to leave their offices and interact with each other. John Lasseter, Chief Creative Officer of Pixar, recalls: „Steve’s theory worked from day one. I kept bumping into people I hadn’t seen for months. I’ve never seen a building that encourages collaboration and creativity like this one.“ After the acquisition of Pixar, Disney adopts some of Pixar’s architectural lessons and opens up the spaces in its huge animation building in Burbank. Steve Jobs later followed the same principle when he designed the new Apple Campus in Cupertino with the help of architecture firm Norman Foster.

Both BMW and Apple put into practice principles of architecture that Thomas Edison used for his innovation management as early as 1887 in the West Orange Lab, his new “invention factory”. Given the crucial importance of communication for innovation, Edison arranged the lab so that the developers conducting experiments in one wing of the building could easily communicate with the machinists making the prototypes in the other wing.

Can digital communications replace chance face-to-face encounters?

In this day and age of multiple digital communication options, we may ask ourselves whether these chance face-to-face encounters are not dispensable. The answer is clearly no. We need to differentiate between communication for inspiration and the other two types of communication: Communication for coordination and Communication for information respectively. Highly complex communications such as those in innovation management require all three types of communication. Although the last two types of communication can now be handled extremely efficiently using digital media, communication for inspiration, which is necessary for the purposes of creativity, still requires chance encounters and face-to-face contact.

Apple’s late Steve Jobs was a firm believer in face-to-face meetings: „In our networked age, there is a temptation to believe that ideas can be developed via email and iChat. That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from chance discussions. You meet someone, ask what they do, you say “Wow” and soon you’re spitting out all kinds of ideas.“

Dr. Rolf-Christian Wentz

Sources:

- Wentz RC (2020) Die neue Innovationsmaschine, Kindle Direct Publishing

- Allen TJ, Henn G (2006) The Organization and Architecture of Innovation. Managing the Flow of Technology, Butterworth Heinemann

- Bock L (2015) Work Rules!, Twelve HachetteBookGroup

- Isaacson W (2011) Steve Jobs, Little, Brown

- Millard A (1990) Edison and the Business of Innovation, The John Hopkins University Press

————————————————————————————————————

7 success factors for innovation teams

Rolf-Christian Wentz

Jan 4, 2023

7 min read time

7 success factors for innovation teams and their design

Optimal team design has a decisive influence on the success of an innovation team. There are 7 success factors for innovation teams – insights from Amazon, Google, Microsoft, P&G, Spotify, Toyota help to optimize innovation team design. The starting point for the considerations here are radical innovation teams. There are a few differences with incremental innovation teams, which I will explain. These are the 7 success factors for innovation teams:

Success factor #1: Small number of innovation team members

The size of an innovation team should not exceed eight people. Ideally, the team should only consist of two to four people, especially at the beginning. Amazon’s motto of the “two-pizza team” is famous. Google is a proponent of a small team size, as it reduces the complexity of interaction and communication and speeds up decision-making. Ex-CEO Schmidt explains: “The best programming team is a ”phone call“ where two people, you and I, program together. The second best programming team is where everyone fits into a single room. All other variants are bad“.

Similarly, Procter & Gamble’s R&D veteran Dirksing, who was part of Crest Whitestrip’s innovation team, emphasizes, “The worst thing you can do in the first part of a project is put a whole bunch of people on it,” he explains. “It’s best to take two people and let them go: an older person for wisdom and advice and a younger person for energy and inspiration.” This statement is supported by some research. It has been found that nowadays researchers have their times of greatest contribution around the age of 36. When a young researcher works with an older colleague with more experience and efficiency, output is maximized.

Microsoft notes that innovation teams developing operational software tend to be larger than application software teams. However, because it favors the entrepreneurial spirit of small teams, it divides large teams into many small teams that have considerable freedom and work in parallel with each other, but must also follow some rules to enforce a high level of coordination and communication.

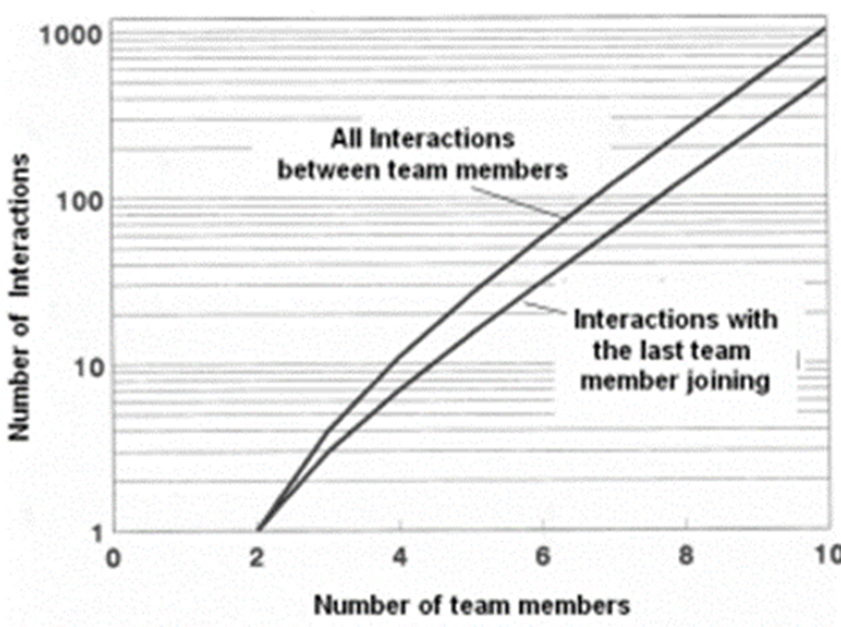

The following illustration shows why a small number of team members is so important: With each additional team member, the need for interaction increases, and this increase is exponential! Each additional team member means a 7% loss in productivity.

Figure: Exponential effect of team size on the number of interactions

Success factor #2: Co-location of the members of the innovation team

Placing the members of a radical innovation team together is a key action to increase the creative and innovative potential of the team. Companies such as Google, Microsoft, Spotify and many others adhere to this principle. Google wants the team members to work in a shared office in close proximity to each other. Google’s ex-CEO Schmidt calls this rule: “Pack them together”.

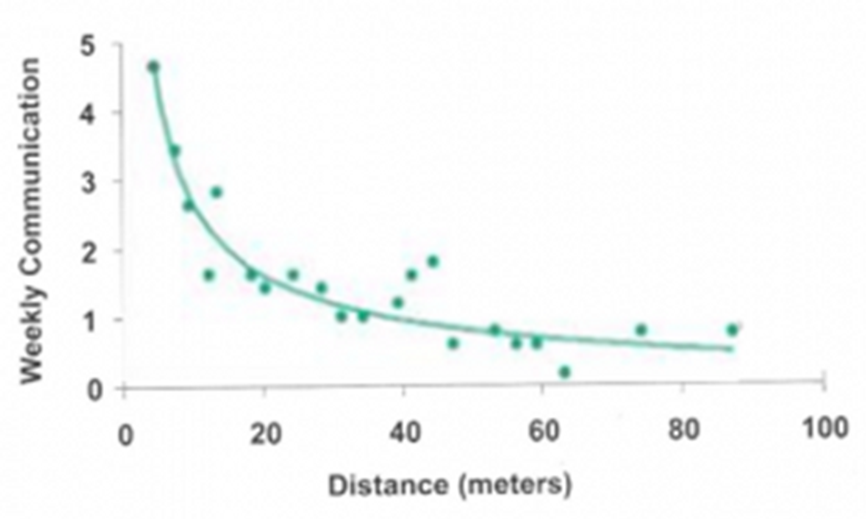

The probability of communication increases the closer the team members work to each other. The effect of proximity on communication is illustrated in the following diagram. At a physical distance of only 30 meters, the likelihood of communication between employees is still very low.

Figure: Probability of communication depending on the physical proximity of team members

However, if the distance is reduced to just a few meters, the frequency of communication increases dramatically.

If, despite everything, a permanent co-location of team members is not possible, it is at least advisable to set up a permanent team room such as Toyota’s obeya, in which the members of the innovation team meet regularly and which is reserved for this one innovation team only.

What also supports the argument for a co-located small team is the importance of direct face-to-face communication in innovation. This form of communication is clearly the most valuable form of communication, ahead of telephone or video conferencing, while email (and similarly chat) is the least valuable. The most successful innovation teams are characterized by the richness of their personal face-to-face communication.

Unlike radical innovation teams, incremental innovation teams often find that the team members are not placed together, but that everyone still retains their workplace in their specialist area. One of the reasons for this is that the exploration phase at the beginning, where face-to-face communication is critical, is extremely short in incremental innovation.

Success factor #3: 100% commitment of innovation team members to an innovation project

In the case of incremental innovations, team members usually only spend part of their time on the innovation project and the rest of their working time on routine tasks.

The demands on the members of a radical innovation team are completely different. Not only in the initial phase is it important that they develop ideas in constant and close contact, implement them in prototypes/MVPs, test them and improve them. In the subsequent phases, too, new challenges constantly arise for which quick and creative solutions must be developed through teamwork. In such an innovation team, it is desirable for the team members to constantly think about their project and consider possible solutions to new problems that arise. This suggests that all team members devote 100% of their time to this one radical innovation project and relinquish their routine tasks.

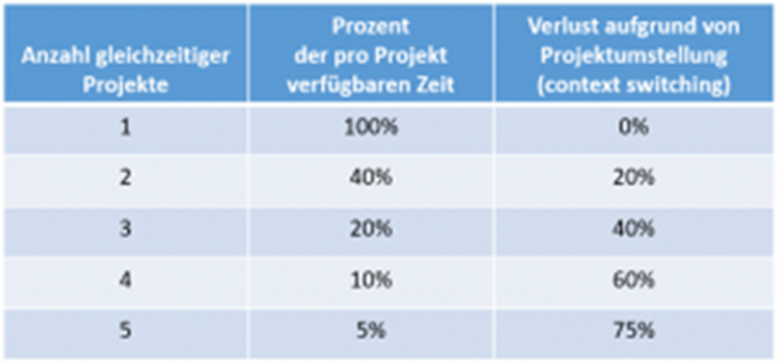

However, this also means that the members of a radical innovation team should only support one radical innovation project and not two or three. If team members were involved in several projects at the same time, their work efficiency would drop and the innovation projects would take longer. This is due to the time lost as a result of a team member having to switch from one project to another and then “find their way back” to the other project. The following figure shows that 20% of the time is lost in just two innovation projects due to the

Figure: Time lost due to switching from project to project

project changeover. In addition to the loss of time, the team member’s commitment is likely to be diluted if there is more than one project. The clear rule for Amazon’s “two-pizza teams” is: “One team, one problem”. Multitasking is out of the question.

In practice, however, such radical innovation teams with 100% commitment from the team members are often not possible due to staff shortages. In these cases, matrix project management is used. The team leader and his team are still responsible for the team’s innovation success, but the team leader is dependent on the heads of the specialist departments or business units to provide him with additional team members. These usually continue to report to the functional or divisional managers in disciplinary terms and are only available to the team for part of their working time.

Matrix project management is Toyota’s way of organizing innovation teams. Only a few employees report to the chief engineer as team leader in a disciplinary and full-time capacity. All other members of his innovation team are only temporarily assigned to him by the project functions, and they only report to him indirectly via a so-called “dotted line”. Toyota sees a major advantage of this organizational form in the fact that the team members remain anchored in their specialist areas and can therefore constantly develop their functional expert knowledge in direct contact with their colleagues in the specialist area.

Success factor #4: Complementary skills of the innovation team members

To maximize the success of the innovation team, the skills of the team members should complement each other perfectly. This applies to both radical and incremental innovation teams.

As far as possible, the innovation team should reflect the competencies that make up the competence model of an innovation champion, i.e. technological competence, market competence, process competence, personal or social competence and leadership competence. Combining all of these competencies in an innovation team is of course easier if the team is somewhat larger. However, if the team only consists of two or three people, each individual team member should have several of these skills. Of course, this also requires luck. It is therefore quite common for small innovation teams to bring in other people on an ad hoc basis as required, who can temporarily provide them with the skills they are currently lacking. This is often the case, for example, if there is a lack of specialist expertise, but can also involve help from an outsider with team moderation, for example.

Even if all innovation teams require a similar basic set of skills, the range of skills sought and the diversity of perspectives brought in tends to be higher for radical innovations than for incremental innovation teams. This is because radical innovation teams also need lateral thinking talent in their ranks, for example, and above all entrepreneurial types. In addition, radical innovation teams, which are supposed to look for completely new solutions, have to overcome the so-called “organizational memory”. This is why there is a strong recommendation to bring in one or two outsiders with experience from another organization and, if possible, a lack of expertise to the radical innovation team. Especially in the current context of digitalization and the formation of agile radical innovation teams, recruiting external people, preferably with start-up experience, is very relevant.

Success factor #5: Commitment of the innovation team to a common mission and the same performance targets

ome innovation teams set their team mission and goals themselves, such as Spotify’s autonomous squads. However, they often come from higher-level management, such as the assignment given to Toyota’s G21/Prius team to develop and launch an environmentally friendly car for the 21st century that will ultimately save 50% of fuel. It is important that the team discusses the mission and performance targets, defines them in concrete terms and makes them its own in the sense of “ownership”. The performance targets that the team receives from outside or sets itself must be output targets and “smart”, i.e. specific, measurable, aggressive yet achievable, relevant and influencable and time-bound.

Success factor #6: Commitment of the innovation team to a standardized procedure

This includes agreements on

- Teamwork: How is the work in the innovation team divided up? Who is responsible for what?

- Administration & logistics: How far in advance should appointments for meetings be made? How should meetings be prepared? How to follow up?

- Rules of conduct: This concerns rules regarding openness, respect, critical questioning, conflict resolution, etc.

- Decision-making: How are decisions made so that all members of the innovation team are behind them? Is unanimity necessary or is a majority sufficient?

- Progress monitoring: How and how often does the innovation team measure the progress of the project? How and how often is external feedback obtained? When should corrective measures be introduced?

- Success factor #7: Joint and mutual responsibility of the members of the innovation team

This means:

Each member of the innovation team has the right to demand from the others their individual performance contributions to the team.

Every member of the innovation team has the right to measure the progress of the team’s work against the mission and performance targets.

Dr. Rolf-Christian Wentz

Sources:

- Wentz RC (2020) Die neue Innovationsmaschine, Kindle Direct Publishing

- Katzenbach JR, Smith, DK (2003) The Wisdom of Teams, HarperCollins

- Allen TJ, Henn G (2006) The Organization and Architecture of Innovation. Managing the Flow of Technology, Butterworth Heinemann

- Hackman RJ (1989) Groups That Work (and Those That Don´t): Creating Conditions for Effective Teamwork, Jossey-Bass

- Schmidt E, Varian H (2005) Google: Ten Golden Rules, Newsweek, 2.12.2005, unter: http://analytics.typepad.com/files/2005_google_10_golden_rules.pdf

- Rigby D, Elk S, Berez S (2020) Doing Agile Right, Transformation Without Chaos, Harvard Business School Press

—————————————————————————————————

Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator

Rolf-Christian Wentz

Jan 3, 2023

4 min read

Tesla’s influence on Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator

If Bosch needed any impetus at all, the cooperation with Tesla, which has long been practising agile innovation management and is seeking collaboration with Bosch because of its Internet of Things (IoT) expertise, underlines the necessity of Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator. Felix Hieronymi, who is tasked by Bosch’s management as project leader with transforming the company into an agile innovator, reports that Tesla, unlike its other more traditional customers, insists on “much more iteration, much more interaction” in the collaborative design and development process of the innovation process and that this demand has “put a lot of pressure on the organization”. Martin Langsch, who has worked for Bosch USA at the Plymouth site since 2011 and is now Engineering Director there, describes working for Tesla like this: “The main challenge is that we don’t know what the final goal is”. Instead of detailed specifications, Tesla has “vision-driven” development orders, such as simply developing a “best of breed” braking system. To meet these requirements and deliver an innovative solution, Langsch’s team primarily uses the agile product development method Scrum. To this end, his team meets with the Tesla managers almost weekly and discusses the current development status of the innovation on the basis of an advanced functional prototype. Thanks to the agile approach, Bosch’s developments for Tesla only take half as long as they would have otherwise.

llustration: Bosch’s cooperation with Tesla (Source: Bosch ConnectedWorld Blog)

Bosch’s transformation into a “dual organization”

Volkmar Denner, who has been CEO of Bosch since July 2012, recognized early on that Bosch can no longer be successful with traditional top-down management in the fast-moving global environment and that agile innovation management is necessary to remain a leader in innovation. Under his leadership, Bosch became an early adopter of an agile mindset and agile methods in innovation management. Initially, Bosch decided to apply agile methods wherever radical innovations were required, while leaving traditional functions untouched. Bosch introduces a so-called “dual organization”. But it does not work.

Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator as a company-wide project

The Bosch Board of Management then decides to turn the agile transformation into a company-wide project led by Felix Hieronymi. The Bosch Board of Management is to act as a steering committee. Hieronymi begins to lead the project as he is used to, i.e. by defining the goals, setting the end date and reporting regularly to the steering committee. But the project makes no progress. The Bosch management realizes that the project approach is not consistent with the principles of agility and that the business units are very suspicious of another centrally organized corporate project. It decides to shelve this approach as well.

The transformation of Bosch’s Board of Management into an agile Executive Action Team

The Bosch Board of Management now decides to no longer act as a mere steering committee, but to work like an agile executive action team itself and to exemplify agility. Meetings of the Board of Management are increasingly becoming stand-up meetings in front of visualization aids on the wall, such as a Kanban board. Annie Howard, a consultant at the consulting firm Bain & Company who is supporting Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator, reports that the board of management „no longer sat behind a big mahogany table and listened to others present in front of them. They stood up, they walked around, they looked at the plans on the wall, they discussed. It was a very interactive, exciting new way of working together“. The management team defines the company’s priorities and ranks them, which are now updated regularly. This allows the team to focus and decide in innovation management where innovation and change are really most important. And it concentrates on removing the biggest obstacles in the organization that stand in the way of greater agility. Rigid annual planning is replaced by flexible, continuous planning with continuous funding rounds. The management is divided into small agile cross-functional sub-teams of 5-6 managers each, who carry out selected tasks. Some of these teams work with product owners, SCRUM masters and sprints, as in SCRUM. „They have personally derived satisfaction from the increased speed and effectiveness. You can’t get that experience by reading a book,“ notes Hieronymi.

Bosch’s 10 new leadership principles

A sub-team of the Board of Management develops a proposal for 10 new leadership principles, which are then published after internal discussion under the title “We lead Bosch” and become binding for all managers. Principles such as “We create autonomy and remove all obstacles”, “We learn from mistakes and see them as part of our culture of innovation” or “We ask questions and give feedback and lead with trust, respect and empathy” must surely sound quite revolutionary to long-serving Bosch managers.

Illustration: Bosch’s new leadership principles “We Lead Bosch”

Today’s status of Bosch’s transformation into an agile innovator

Today, Bosch consists of many divisions that rely on agile innovation teams and have already reached different levels of agility, such as Bosch Software Innovations, the Power Tools division, in particular the Home & Garden product area, and the Bosch subsidiary ETAS. On the other hand, there are still some more traditionally structured divisions. However, almost all of them have adopted agile values, have improved cooperation between their associates and are adapting more quickly with innovations to the increasingly dynamic changes in the market.

Dr. Rolf-Christian Wentz

Sources:

- Wentz RC (2020) Die neue Innovationsmaschine, Kindle Direct Publishing

- Howard A (2018) Agile Transformationat Bosch, Scrum@SCALE 27.2.2018, unter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYpAVKgqFig

——————————————————————————————————–

Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany

Rolf-Christian Wentz

Jan. 4, 2023

8 min. reading time

Established German companies (corporates) increasingly understand that they need to become more agile in innovation management. Digitalization is often the trigger. Start-ups serve as a role model for corporates. Start-up contacts are becoming increasingly important. Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups are moving into focus. On the one hand, in the sense of open innovation, e.g. to gain access to new technologies and business models. On the other hand, to inspire one’s own organization through the start-up culture, which often results in the founding of internal start-ups, which in turn inspire the general innovation management of the established company. I have already described the development of an agile innovation culture with the help of start-ups and the success factors of agile innovation teams elsewhere (see below). Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany is the subject of this article. It is about special alternatives for the innovation organization.

Example: External start-up

On November 17, 2017, Daimler AG will open the Mercedes-Benz Research & Development Center in Tel Aviv, Israel, as part of its global R&D network. The aim is to develop technologies for the connected vehicle in collaboration with external Israeli start-ups, among others. One way of cooperating with these start-ups is via the accelerator “The Bridge”, which Mercedes-Benz supports as a sponsor and for whose seven-month program the agile start-up Anagog, founded in October 2010 by Gil Levy and Yaron Aizenbud in Tel Aviv, has also registered. The accelerator program of “The Bridge” offers participating start-ups – in addition to training and coaching – access to managers from sponsors such as Mercedes-Benz. Anagog’s cooperation with Mercedes-Benz leads to the new EQ Ready App, which both partners are developing together in less than 5 months. This app supports drivers in deciding whether they should switch to an electric car or a hybrid vehicle. On February 26, 2018, Daimler’s corporate venture fund invests in a Series B financing round.

Example: Internal start-up

In March 2017, Florian Ade and Julian Fieres ask themselves why optical sensors such as radar or lidar are used in modern vehicles, but not acoustic sensors. Ade is Senior Manager Corporate Strategy at ZF Friedrichshafen AG and has been with ZF since 2014. Fieres is Head of Strategy, Business Development and M&A in the E-Mobility Division of the ZF Group and has been with ZF since 2013. Both are convinced that hearing is an important safety factor in road traffic. If the driver has loud music on in the car, a microphone should be able to warn them in good time of an approaching fire department. And if an ambulance is approaching, the sensor should help to recognize which direction it is coming from. As the technical solution requires artificial intelligence, Ade and Fieres call their internal start-up Sound.AI. In July 2017, both took part in ZF’s internal Innovation Challenge 2017. They won, received an initial investment from ZF and founded their agile internal start-up team. Within a few months, they use the agile methods of a lean start-up to build a minimum viable product (MVP), which passes its first practical test shortly before Christmas. ZF then decides to develop the product until it is ready for series production.

Countless opportunities to contact start-ups

There are countless ways to get in touch with start-ups. This article focuses on four structural alternatives for organizing innovation: incubators, accelerators, corporate venture funds, innovation competitions and hackathons.

Incubator and accelerator

Incubators and accelerators basically pursue similar goals. However, while new business ideas are born and gradually developed in an incubator such as VW’s “Digital:Lab”, for example, the focus is on the exploration phase of the innovation process, an accelerator such as SAP’s “IoT Startup Accelerator” is intended to drive and accelerate the scaling of an existing start-up by providing additional resources and access to sales, customers and possibly even the technology and data of the established company. A second difference between the two forms of organization is that the time in accelerators is usually limited to 6 months for start-ups, while incubators often have no time limits, but the end of the project occurs when the idea is no longer considered worth pursuing. Many companies combine incubators and accelerators so that they merge, as Bosch’s intrapreneur platform “Grow” does, for example.

Incubators and accelerators can differ in terms of the mix of innovation teams they accept. There are basically three different types: They can exclusively support internal teams. Or exclusively external start-up teams. Or a mixture of both. In practice, incubators predominantly take on internal innovation teams, while accelerators almost exclusively support external innovation teams that contribute their external, often disruptive ideas. Accelerators are therefore particularly suitable for the development of new business models, which are currently becoming increasingly relevant in the context of digitalization.

Incubators and accelerators in which internal innovation teams work directly alongside external start-ups, such as the “Leaps by Bayer” incubator, are very effective. This allows the internal teams to get to know and internalize the way of thinking and working and, above all, the start-up culture of the external teams.

Companies can have their own incubator and/or accelerator. Many companies, especially smaller ones, prefer to participate in an incubator or accelerator, e.g. the “InsurLab Germany” incubator in the insurance industry or the “Startup Autobahn” accelerator in the automotive industry.

Corporate venture fund, innovation competition, hackathon

A special organizational form of innovation management is a corporate venture fund (CVF) such as Siemens‘ Next47 Fund, which provides EUR 1 billion in capital for external investments over 5 years. CVFs are autonomous business units that invest corporate venture capital (CVC) in innovative and promising external start-ups and provide them with long-term support. Companies can have their own CVF. However, many companies also participate in external venture funds such as the High-Tech Gründerfonds.

Innovation competitions such as ZF Friedrichshafen’s Innovation Challenge, at which the two founders of the internal start-up Sound.AI presented their innovative acoustic sensor in the final “Pitch Night”, have relatively narrow topics. The teams usually have several months to develop their solution.

In hackathons, on the other hand, teams usually develop prototypes of new software or hardware in 24- to 48-hour sprints. The task is broader than in innovation competitions. Hackathons such as those organized by Allianz or Deutsche Telekom, in which the company’s own teams usually also take part or in which its own employees at least come into contact with external teams, are good examples.

Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany: the state of development

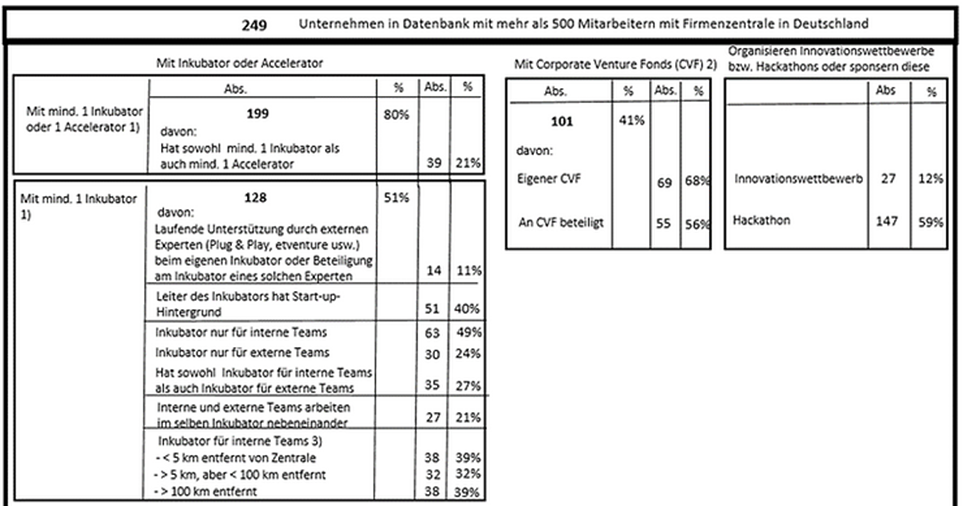

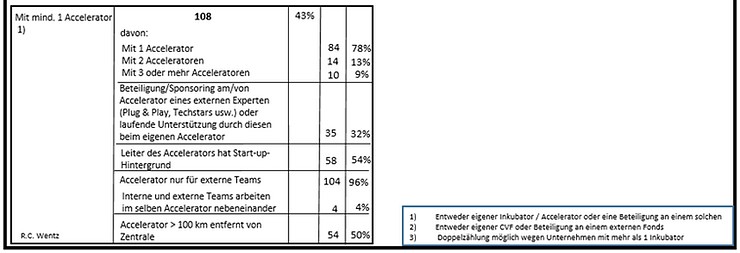

As of June 2021, we have identified and examined 249 companies with more than 500 employees and headquarters in Germany that practice open innovation and have contacts with start-ups in the form of incubators, accelerators, corporate venture funds, innovation competitions or hackathons.

Figure: Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany

Of the 249 companies with headquarters in Germany, 199 (80%) (e.g. Boehringer Ingelheim, Thyssen-Krupp, Wilo) have at least one incubator (also known as an innovation lab, company builder or innovation hub, depending on its form) or accelerator (e.g. Adidas, Deutsche Bahn, EOS) or hold a stake in one. 75% (150) of these 199 companies have only founded or acquired a stake in the incubator or accelerator since the beginning of 2016. 7% (17) of the 199 companies have only joined in the last 9 months. Of the 199 companies, 39 (21%) have or are involved in both an incubator and an accelerator.

128 (51%) of the 249 companies surveyed have at least one incubator of their own or are involved in one, such as the “InsurLab Germany” incubator, which has many members from the insurance industry, such as ARAG, Debeka or Gothaer Versicherung. 108 (43%) have at least their own accelerator or – and this is the vast majority – are involved in one, such as the

- Accelerator “STARTUP AUTOBAHN” with partners such as Daimler, ZF, BASF, Porsche, Deutsche Post DHL, Webasto, Benteler, Hella, Linde

- Accelerator “Beyond1435 Open Innovation Platform”, in which e.g. Deutsche Bahn, Siemens, Alba, TUI are involved,

- “Next Media Accelerator”, whose partners include dpa, Axel Springer, Funke Medien, Die Zeit, Madsack, media + more venture and the Spiegel Group,

- “Next Commerce Accelerator” with partners such as Beiersdorf, J. Darboven, Edeka, Tchibo

- “Next Logistics Accelerator” with investments from Fiege, Jungheinrich, Helm, HHLA, Körber, Rhenus

- “M.Tech Accelerator”, in which e.g. ENBW, Daimler Financial Services, Deutsche Bank, Festo, Kärcher, Mahle, MBtech, Recaro, Bosch, Software AG, Trumpf, Deutsche Telekom,

- “Universal Home Accelerator” with partnerships from Miele, Gira, Poggenpohl, Vaillant, WMF, Dornbracht

- Accelerator “Seedhouse” with 32 participating partners such as Apetito, Berentzen, Big Dutchman, Coppenrath & Wiese, Grimme, Homann, Krone, Lemken, Wiesenhof.

Of the 108 companies with an accelerator or participation in an accelerator, 14 companies are partners or owners of two accelerators, while a further 10 companies, such as Bosch or Daimler, even own three or more accelerators.

39 (21%) of the companies, such as Trumpf, Zalando or ZF Friedrichshafen, have at least one incubator and at least one accelerator or are involved in such.

Only 11% of companies with their own incubator or a stake in one, including companies such as Alba or SMS, are supported by external experts (e.g. Plug & Play, etventure, etc.) in the ongoing operation of their own incubator or participate in the incubator of such an expert. Partnerships with these external experts (Plug & Play, Startupbootcamp, Rocketspace, TechStars, etc.) are much more common among accelerators. 32% of companies rely on their ongoing support (example: the Startup Autobahn Accelerator, supported by Plug & Play) or participate directly in the accelerator of such an expert.

One success factor for incubators and accelerators is if the manager has a startup background and can therefore convey the culture and working methods of startups from their own experience. This is practically always the case with incubators and accelerators run by external experts, in which companies can participate. Including these, 40% or 54% of companies with an incubator or accelerator have such a qualified manager with a startup background.

Of the 128 companies with an incubator or a stake in one, 63 (48%) have an incubator for internal teams only, and 30 companies (24%) have an incubator for external teams only or a stake in such an incubator. 35 companies (27%) have an incubator for both internal teams and an incubator for external teams, or at least have a stake in one. Of these 35 companies, 27, such as Bayer, Gruner + Jahr or Deutsche Bank, bring external and internal teams together in their incubator or the incubator in which they are involved, thereby accelerating the learning process of the internal teams.

Of the accelerators, 96% are reserved for external teams. Only 4% of companies (e.g. EON, Siemens, Osram) have an accelerator or are involved in one in which internal teams also work alongside external start-ups, thus promoting the transfer of learning.

In the case of start-ups, the question arises as to the optimal distance between the location of the start-up and the headquarters of the established company. On the one hand, start-ups should be far enough away to be able to develop completely new and, if possible, disruptive ideas. On the other hand, they should be able to access the resources of the corporate partner, which speaks for good accessibility. It can be assumed that incubators, which primarily support internal start-ups, are not located too far away, while accelerators, which are essentially created for external start-ups that are expected to come up with disruptive ideas and business models, are located further away. This hypothesis is only partially confirmed. 39% of companies such as B. Braun or Claas have incubators less than 5 km away from their headquarters, 32% of companies such as ENBW or KSB have incubators more than 5 km and less than 100 km away, and 39% of companies such as Klöckner or Lenze have their incubator more than 100 km away. Of these distant incubators, 47% are based in Berlin. In the case of accelerators, 50% are more than 100 km away from the company headquarters, and 43% of these are in Berlin.

101 or 41% of the companies surveyed have their own corporate venture fund or are involved in a third-party venture fund. 68% of the 1010 companies have their own fund or 56% are invested in an external venture fund.

12% of German companies organize or sponsor innovation competitions to present prototypes of proposed solutions to specific issues, and 59% organize or sponsor hackathons in which internal teams usually participate alongside external teams.

Corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany: the bottom line

German companies are making great progress in using start-up contacts to become more agile in their innovation management. More and more companies are using innovation organization alternatives such as incubators, accelerators, corporate venture funds, innovation competitions or hackathons. There is a strong tendency towards cooperation, especially among medium-sized companies, in order to be able to use incubators or accelerators efficiently together, for example. However, when it comes to corporate innovation management and open innovation with start-ups in Germany, there is considerable untapped potential to consolidate and accelerate the transformation to an agile innovator through the simultaneous use of the five organizational alternatives.

Dr. Rolf-Christian Wentz

Sources:

- Wentz RC (2020) Die neue Innovationsmaschine, Kindle Direct Publishing

- Wentz RC (2020) Start-up-Kultur verändert Unternehmen. Wie arrivierte Unternehmen agile Innovationskultur schaffen, OrganisationsEntwicklung, Nr. 4/2020, S. 114-116

- Wentz RC (2023) 7 Success Factors for Innovation Teams, see above

- Romans A (2016) Masters of Corporate Venture Capital, CreateSpace